"We leave design to the designers."

If you're accountable for the business and that's how you think, there's a high chance your project will end as nothing more than a beautiful concept—great on paper, powerless in the real world. Because design is not merely the act of polishing surfaces.

Design is an integrated practice: it carries aesthetic intent, forms a plan, becomes a lived experience, works as a business, and ultimately gets implemented in society. On that long and demanding journey, one question matters more than most:

Who makes the crucial decisions?

Drawing on the curriculum of FOURDIGIT Service Design School and real projects we've seen firsthand, let's unpack the answer.

1. Design Is Social Implementation

Many people still equate design with "creating a blueprint" or "making something beautiful." That isn't wrong—but it's only a fragment of what design actually is.

Even the most elegant concept can fail to reach society if it's technically unfeasible or cannot sustain itself as a business. In that case, it becomes a gorgeous prototype collecting dust in the corner of a room.

For us, design means completing all three of the following:

- Aesthetic Planning (Plan): imagining a future that enriches people's emotions and everyday lives.

- Experience Realization (Realization): turning ideals into something that actually works—an experience people can use.

- Business Implementation (Implementation): making it profitable, sustainable, and truly adopted in society.

But the moment you connect these three, contradictions appear—inevitably.

The "ideal experience" conflicts with development cost. Local craft and aesthetic judgment conflict with deadlines. In that tension, deciding what to protect—and what to compromise—cannot be the designer's job alone.

2. The Collision of Three Dynamics

In modern service development, three forces are always pulling in different directions:

- BUSINESS dynamics: revenue, profit, efficiency.

- TECHNOLOGY dynamics: feasibility, stability, constraints.

- DESIGN dynamics: human emotion, usability, taste.

Left unattended, these forces create deadlock. Business says, "Add features so we can sell." Engineering says, "Play it safe." Design says, "Make it the experience users actually need."

Breaking that stalemate—making a judgment like "This time, we prioritize user trust over short-term sales"—requires someone who holds responsibility for the whole business.

That person is the business leader.

3. Case Studies: A Leader's "NO" and "Will" Shape the Future

Let's look at two real examples where leadership decisions determined whether a design truly became social infrastructure—or remained an idea.

Case 1: Japan Post Bank Passbook App — The courage to decide "not to do"

In the development of Japan Post Bank's app, the business side initially had a strong request: "We want to promote financial products like loans and investment trusts. We want to sell."

But user research revealed something crucial. Many users were not highly financially literate, and most simply wanted one thing:

To check their balance and transaction history.

At that moment, the team held back the business pressure to "sell," and made a decisive call:

Focus relentlessly on a simple 'balance check' experience.

This wasn't just a UI decision. It was a strategic, executive decision about what the product should be in society.

Instead of building a "rich, feature-heavy app" (addition), they chose to build an "infrastructure anyone can use" (subtraction).

The result: despite being far simpler—and, on paper, less "competitive" than other banking apps—the app became a widely used social utility with over 13 million accounts, reaching that scale quickly and maintaining a strong level of active use.

Case 2: AEON Wallet — Leadership breaks through design's limits

In a renewal project for AEON Financial Service's payment app, the executive leader made their intent crystal clear:

"Don't make something ordinary."

This wasn't motivational fluff. It was a rejection of industry assumptions—"This is what a payment app should be"—and a refusal to hide behind precedent as a safe choice.

Because the top leader signaled a willingness to take risk, the team could go beyond "requirements" and seriously pursue a deeper question:

What does comfort feel like for the user?

The outcome was a payment app experience that, unusually for the category, allowed users to feel, "This fits me," and even "I'm attached to it." It helped attract new customer segments, including younger audiences. And through post-payment interactions, it also significantly increased traffic to other services in the ecosystem.

4. What Business Leaders Must Do

Learning design skills takes time. But leaders don't need to become designers.

What leaders must do is respect designers as true professionals—and fully leverage their capabilities in the business arena.

Here are three actions that matter.

1) Bring designers in from the start

Many teams involve designers only after requirements are fixed—asking them to "make it look good at the end." That is almost always too late.

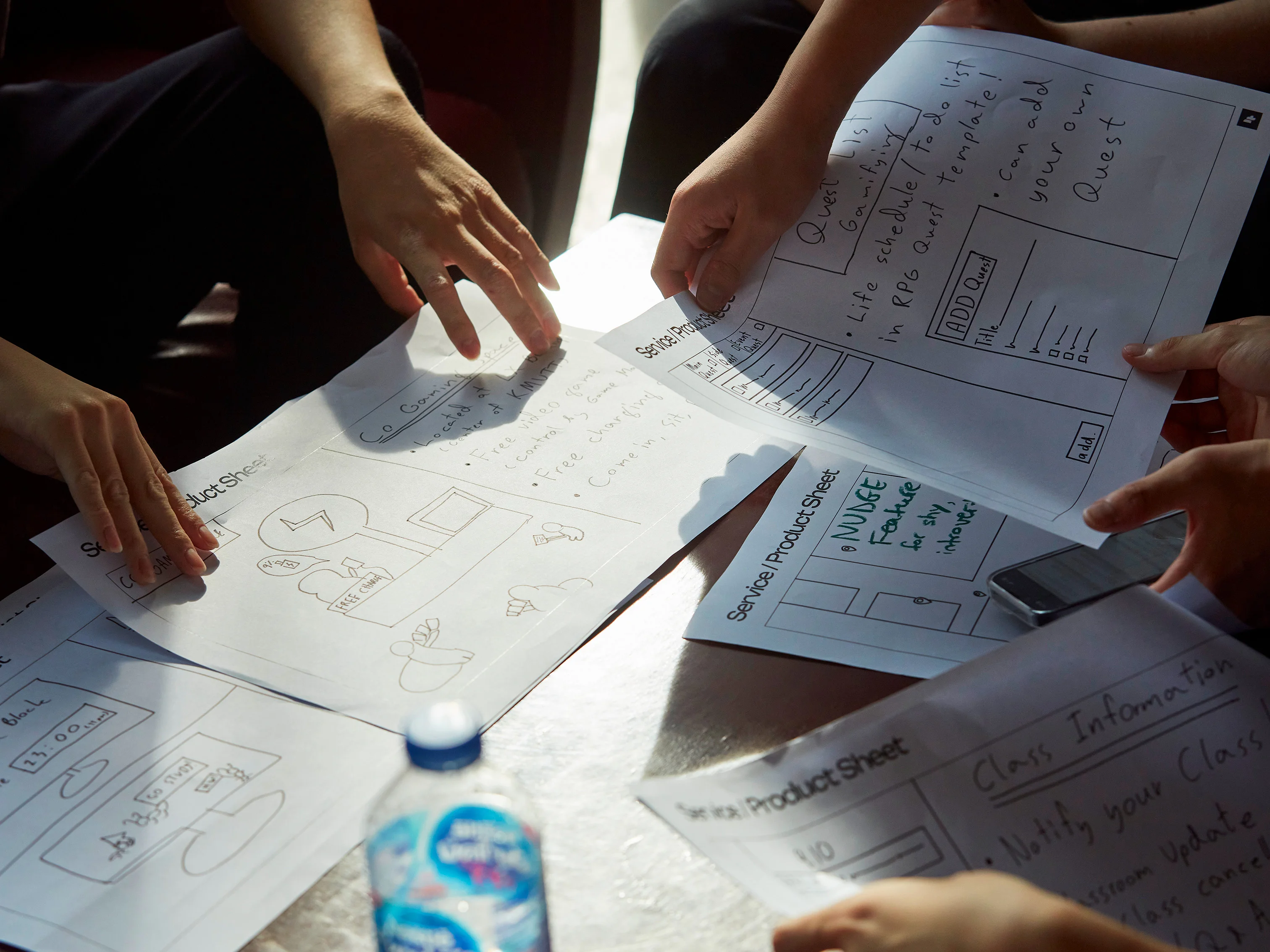

Bring designers into the concept stage, where you decide what to build in the first place. Designers have the ability to translate vague business problems into concrete options. Early involvement reduces rework and increases the chance of reaching a more fundamental solution.

2) Use design as a shared language

When business and engineering conversations don't align, design becomes the bridge.

By visualizing complex discussions and building tangible prototypes, teams can align understanding across roles in an instant. Treat design not just as deliverables, but as a communication tool that accelerates alignment and decision-making.

3) Bring "facing the user" into business decisions

Business environments often default to seller logic—numbers and efficiency.

Designers are trained to observe human emotion and behavior, and to think from that reality. The leader's role is to bring that user-facing capability into executive rooms and decision tables—so "customer truth" doesn't get lost behind dashboards.

5. Conclusion: Design Is the Will to Break Through Reality

In the design process, the phase that most often becomes the hardest decision-making point is Verification—the moment when your ideal future collides with cost, schedule, and organizational constraints.

This is where teams hit the wall: "The budget doesn't work." "There's no precedent." The idea gets rounded off, softened, and quietly turns into a "safe service."

And then it stops mattering.

Don't just adjust—commit

A business leader's role is not to simply manage consensus and keep everyone comfortable. Under real constraints, the leader must protect a line:

"Even so, this experience is non-negotiable."

Design's role is to show the path—facing the user even within constraints, and presenting credible routes to realization.

Design is not drawing a pretty picture. It is the refusal to let go of aesthetic and human intention—even when reality is irrational and messy—and the commitment to implement a better future in society.

The people who can hold that will, and decide with it, are the ones who change business—and society.

This article is based on content from FOURDIGIT Service Design School.

For more details, please feel free to contact us.