Design thinking textbooks and many business books love tidy process diagrams. Start with research, generate ideas, develop, release—moving left to right along a clean, beautiful flowchart.

But in real business projects, it's rare for work to progress exactly as those diagrams suggest.

Because a design process isn't a formula that produces a single correct answer. It is the work of finding an answer where no single "right" answer exists.

Based on the curriculum of FOURDIGIT Service Design School, this article explains why the process is never elegant—and what to do about it.

1. "Optimization requirements" from different angles

In modern service development, you always have to consider three elements:

- BUSINESS requirements: sustainable profitability, ROI, market share

- TECHNOLOGY requirements: feasibility, security, system stability

- DESIGN requirements (experience): usefulness, psychological satisfaction, brand value

These aren't necessarily "in conflict." The real issue is that their optimization goals can be different.

If the business side aims to maximize profitability, cost reduction and price optimization naturally become priorities. If the design side aims to maximize experience, investment in quality may be necessary. And when it comes to security concerns, you can keep investing forever and still feel it's not enough.

Because these structural trade-offs exist, it's actually healthy when a process slows down or discussions become complex. It doesn't mean the team is lost—it often means each standpoint is simply arguing for what it believes is necessary, rather than rushing forward based on only one requirement.

2. "Verification" as an iterative movement

To organize this reality, our process includes a phase we call Verification (validation / definition).

You can't hand an ideal concept directly to development. Before that, you must test it against technical feasibility, effort and schedule, and business viability.

- "With our current tech stack, we can't deliver this experience at a viable cost."

- "If we cut cost enough, the user value collapses."

At this point, we may return to earlier decisions, adjust parameters, or explore alternative approaches. From the outside, it can look like we're "going back and forth."

But this iteration is not waste. It is the essential work of reconciling contradictory conditions and finding a landing point that can actually be implemented. A non-linear process is not a sign of failure—it is intellectual exploration aimed at producing a higher-precision blueprint.

Ironically, believing the work should move in a straight line often creates the real problems: people misinterpret rework as failure, learning stops, team morale drops, blame begins to circulate—and nothing good comes from that.

3. User-centeredness as a rational decision-making standard

So when trade-offs become difficult and the team can't decide—what should guide the decision?

In reality, decisions can be influenced by internal power dynamics or personal preference. But the goal that most people can align on is simple:

Deliver the best possible experience for users.

That's where a User-Centered approach works. This is not a philosophy or a motivational slogan. It is an extremely rational method: use "user facts" as a shared decision standard.

For example, suppose prototype testing shows that "Option A converts better than Option B." With that objective fact, business and tech can look in the same direction and form agreement. And if user verification shows the service simply doesn't work, the team can shift the conversation to what must change at the system level.

User-centered design is, in that sense, the most rational decision-making system for aligning perspectives and moving a project forward in complex conditions.

And importantly: users don't always hold the answer. Even then, the team can still debate with a shared lens—what is most optimal for users?

4. An exploratory approach in design work

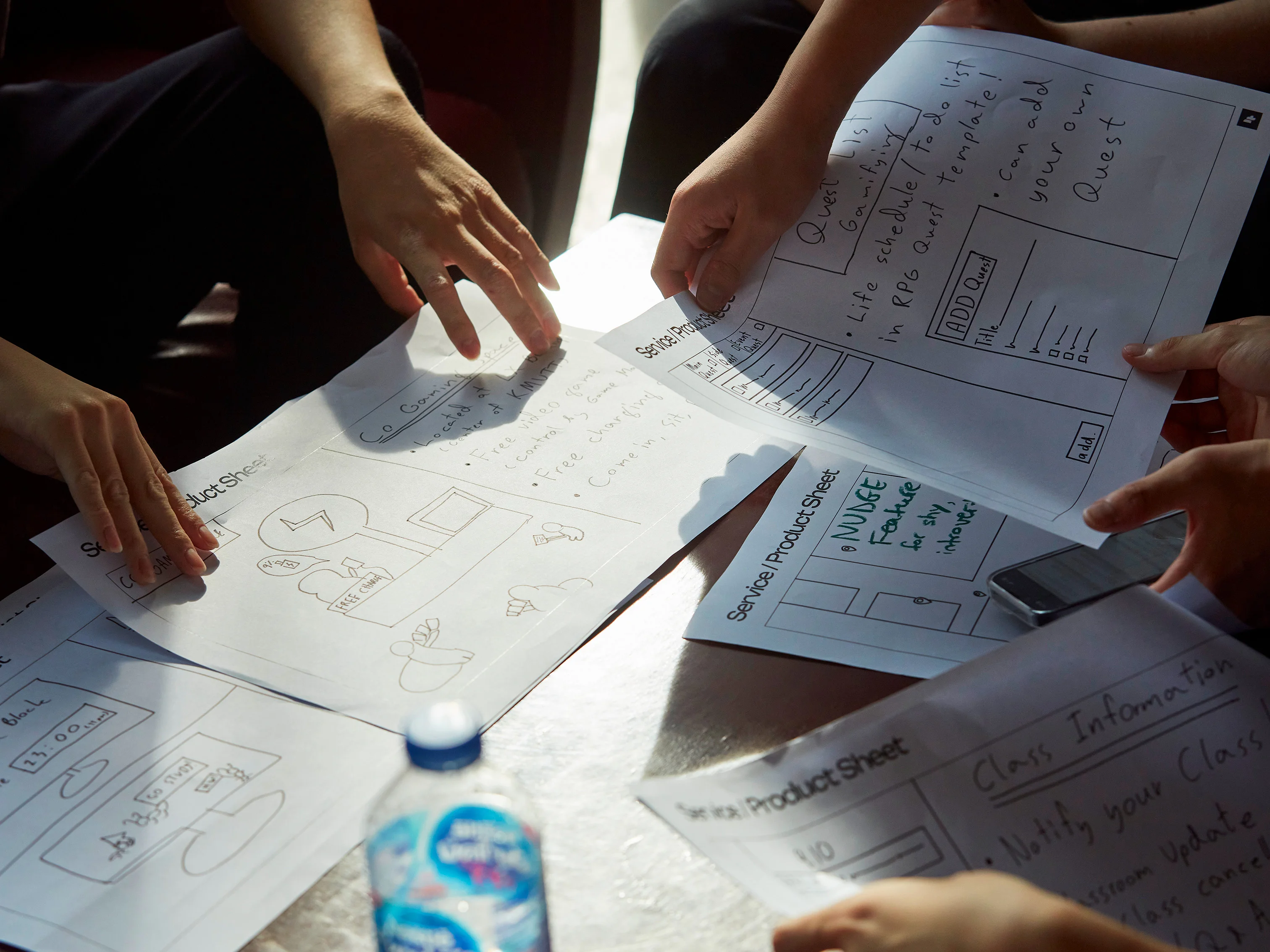

Even in the phase where designers "make," work rarely progresses in a straight line.

Design is not the act of outputting a perfect vision already completed in your head. It is repeated exploration—build, think, break, rebuild.

Imagine you're designing a UI screen. It may look beautiful and functional on its own, but once you connect it to surrounding screens you may realize the flow feels unnatural. Or when you refine the details, you may uncover contradictions with the original concept.

- "To preserve overall coherence, we discard something we already made."

- "We try alternative patterns and compare."

This build-and-return iteration is not wandering. It is the process of sharpening abstract ideas, resolving contradictions, eliminating discomfort, and elevating the output into something truly strong.

5. "Technical dialogue" in the development phase

The same dynamic appears in engineering.

Development is not as simple as writing code exactly as the specification says. As implementation progresses, teams routinely hit technical walls: performance issues, unstable behavior under certain conditions, unexpected constraints.

At that moment, engineers don't simply stop. They trace the process back in search of solutions.

- "This library can't support what we need—we must change the design."

- "Is there an alternative that preserves the experience while reducing implementation load?"

Engineers then re-enter dialogue with designers and business stakeholders, redefining stronger specifications and requirements. This feedback-driven rework from implementation is precisely what prevents a project from ending as a "drawing on paper," and enables it to be implemented as a robust, working service in society.

6. Conclusion: The will to face reality—and the team that sustains it

In design processes, things don't move in a straight line. Coordination takes time.

But that often means the team is refusing shallow compromise—and instead trying to satisfy business, technology, and design requirements at a high level. Patiently untangling complex variables and finding a landing point worthy of being called an optimal solution—this intellectual endurance and will is the path to implementing competitive services in society.

This persistence is not elegant. People who don't understand it may even wonder what you're doing.

Yet we also know this: the difference between something crafted with conviction and something done carelessly is visible to customers.

And over time, a professional stance toward iteration itself accumulates as a capability—and becomes real value.

This article is based on content from FOURDIGIT Service Design School.

For more information, please feel free to contact us.